- Home

- Mary Hagen

Forbidden Love Page 2

Forbidden Love Read online

Page 2

He stood and faced Dr. Dresser. “Hannah and I will continue to see one another. Neither you nor my family nor the Nazis can tear us apart.”

His life would not be easy or simple but he could not stay away from Hannah. His broad shoulders sagged under thoughts of what they would face, face together as man and wife. They would marry in Switzerland even though the country remained on friendly terms with the Nazi Government. All marriages between ethnic Germans and Jews had been banned. Pure Germans married to Jews had been ordered to dissolve their marriages and abandon their children. He vowed to himself, Hannah and he would marry and never separate, Hitler be damned. No one needed to know.

“Hannah, my love, get your coat. We’ll take a drive. We have much to discuss.”

She glanced at her father and her mother. Her father scowled his disapproval with such severity his message was evident. Break away from Penn. Her mother returned to her reading without comment or signal of her thoughts.

Together, they walked through the great room, furnished with dark mahogany chairs and tables, the floor covered with an expensive Persian carpet much like his home. They went to the front hallway and retrieved her dark wool coat from the closet. Penn glanced up the curved staircase in search of Jacob who approved of his relationship with his sister, Hannah. He was nowhere in sight. Stepping out of the carved oak front door, Penn did not care if his father spotted them together. He tucked her arm under his, her slim body pressed against his side. She was his love the only woman he would ever love.

Chapter 2

The day was warm. Sunlight highlighted windows in the buildings and trees along the street. Hannah noticed none of it as she walked along the sidewalk, the smell of exhaust from cars, the honking of horns, the chatter of people. A hard lump of fear contrasted with outrage stuck in her chest. With her head bowed, she avoided looking at people she passed. Her sack containing a few belongings as well as her nurse’s uniform bounced against her leg. With a quick swipe of her hand, she wiped the tears from her cheek.

She had lost her job. The hospital administrator, Dr. Franz, informed her in words that hurt. They pounded in her ears and added to her fear.

“You’re a Jew. How we overlooked that when we hired you is a mystery. You cannot work in this hospital.” He faced her, his hands interlaced under his chin, his expression and eyes displaying his contempt. “You are nothing, a varmint. Pick up your belongings and leave.” He wrinkled his nose and sniffed as though she smelled and turned away from her.

His words stung into the deepest part of her stomach. She had the greatest respect for him. His words, his rejection wounded her. Her first reaction was to lash out at him. She held her tongue.

Picking up his pen, he treated her as though she no longer existed. In his mind, she did not, not as a person, but as the scum of the earth. Her loyalty, her competency, her work ethic were nothing to Dr. Franz. Her thoughts darkened and sharp stabs of sadness brought tears into her eyes.

As Hannah left his office, she felt her nose with her free hand. It was not large, didn’t have a hook, and wasn’t hairy. Neither was her face. She ran her finger over her mouth. Her lower lip did not protrude. Cold filled her lungs. Was this some sort of game? No. For the first time, she was afraid. The warmth of the room did nothing to erase her anguish.

Before leaving, she collected her belongings and stopped at the nurses’ station to say goodbye. The women, one by one, swiveled in their chairs and concentrated on desk duties, avoiding her. She blinked to hold back her tears. They were no longer her friends. She left quietly with a sense of oppression she could not shake.

She ran into Mrs. Berger, the head nurse, who had praised her work, but Mrs. Berger shoved hard against her shoulder as she walked past her knocking her to her knees. “Glassy-eyed rat,” she said.

Picking herself up, Hannah, dressed in her green tweed skirt and a plain white shirt and brown sweater, continued for the exit. Her heart thumped with regret. She loved her work with patients, and she would miss them. Would they miss her? She knew she was excellent at her job, better than most. Her eyes were blue, not glassy. She touched her nose again. It was small and straight. A sob jammed her throat. She forced it down and walked fast along the hallway to the lift, anxious to get away from the accusing eyes of her fellow nurses whom she had considered her friends. Dr. Hoffman brushed by her without glancing up from records he held in his hands, the doctor who asked for her when he needed assistance.

He paused and touched her arm to stop her. “I’m sorry, Hannah, but I can do nothing to change the orders and help you. I’ll miss you.” He nodded and continued along the hallway.

Home offered safety. Safety, in Germany, there was no safety for a Jew. Her father could no longer practice medicine. Before the Nazis declared Jews noncitizens, before Hitler disenfranchised them, her father was one of the best physicians in Berlin. In 1935, the Nuremberg Laws stripped the Jews of citizenship. The Jews were blamed for the loss of the great war and the depression rocking Germany. How could they? They were good loyal Germans.

At great risk, her father continued to practice medicine, but his patients were Jews. Many could not pay him for his services having lost everything. She would help him. She was an excellent nurse, considered outstanding until it was discovered she was a Jew. Tears threatened to surface. Helping her father was a refuge but not what she wanted. She liked the routine of the hospital, the excitement of emergency cases, the life and death struggles that occurred every day.

Storm Troopers had daubed yellow paint on her father’s office. They had positioned themselves in front of his entrance and demanded people boycott him. Non-Jewish doctors, his friends and co-workers, did not support him, ignored him, but many of his German patients continued to come to him until he lost his license. Some were embarrassed and told him so but informed him they could no longer associate with him for the safety of their own careers. He was forced to close his office and clinic and open rooms in their home.

All Jews lived in fear. Every day she left home her fear surfaced. Her life had descended into a deep hole. The laws as written allowed Gestapo, Storm Troopers, and German citizens to do as they pleased to a Jew. Jews were outlaws, the scum of the earth, not human.

Hannah left the busy street to cut through a corner of the wooded Tiergarten, Berlin's beautiful park, but before she did, she paused to observe Storm Troopers pushing a young woman ahead of them, hitting her with batons, and yelling obscenities at her for loving a Jew. A noisy crowd followed the Storm Troopers taunting the woman. Hannah froze, afraid for the young woman, but powerless to help. She fled into the park, a place of refuge for her, but thinking she was a coward. She should have gone to the woman and dragged her away from the police. And been tortured too.

Although the day was warm and sunny, coldness ran through her blood. Her father was correct. She must tell Penn she could no longer see him, leaving a void in her life. The thought aroused her nerve endings in a tangle of conflicting emotions of love, anger, regret, and guilt. How could she separate herself from him? Her knees buckled. She found a bench and collapsed onto the seat. Her dreams had to be abandoned. Life with Penn was no longer possible. She put him in danger, his career in the Luftwaffe, and that of his family. Her lips trembled and a cry of anguish slipped out of her throat. She did not have the strength to leave the bench even though the evening grew dark and the air cold. Her love for Penn was so deep, it tugged at her heart and tied her stomach into knots.

Two Gestapo walked past her. One whistled, paused, and said, “Is everything all right? You wear such a sad expression for such a beautiful German maiden.”

“Yes. Thank you. I’m weary after a busy day and I’m taking a rest.” She forced a smile terrified he might notice she was a Jew. “I’m a nurse and we had a sad case today.”

“What is your name?”

“Nixie,” she lied. She

was powerless to answer with anything but a lie.

“And your last name?”

“My husband might object to giving my name to such a handsome man as you.”

The man grinned. “I understand.”

He joined his companion and they continued patrolling the area. Hannah grabbed the handle of her sack then forced herself to stand and move her feet in the direction of her home. The Gestapo did not notice she was a Jew, but she could not erase who she was. A nightmare was her constant companion.

Her home stood in the middle of the tree-lined street with large houses on large lots. Her residence was dark unlike other homes in the area including the next-door neighbors, the Schwartz's. She opened a wrought-iron gate, walked toward the double front doors, made a turn and proceeded to the back door wondering if Penn was home from his day flying his plane. Hurt surfaced. Pain clutched her heart. She must no longer think of Penn after tonight, after she told him she could no longer see him. She shuddered with sadness.

Since she’d been a child, she had tagged after her big brother, Jacob, and his best friend, Penn. Sometimes, they tried to ditch her, but when she fell too far behind them, they relented and waited. She hadn’t liked Penn until he returned from the university in his senior year. He had changed and she fell head over heels in love with him. It was mutual. When he returned to his lessons and she to her studies in nursing, they promised to remain faithful to one another.

Her distress intensified as her memories with Penn turned dark with uneasiness. Her life had become one of dodging unimaginable shadows with unknown hazards she could not finger.

Mrs. Oster, Ethel, the only servant still with them, stood at the stove stirring soup, the delicious smell wafting into the air meant to entice taste buds but instead upset Hannah’s stomach.

“Hannah, dear, you look so stressed, so cold. Let me take your sack. You sit and I’ll pour you some coffee.” She pulled out a chair at the kitchen table.

“Where’s Papa?” Hannah needed to see him, inform him of the loss of her job, and her decision to follow his advice as much as it pained her to lose Penn.

“He’s still seeing patients. I believe he has two to attend. He’s had a busy day.” She shook salt into the soup. “How sad, he had to close his office and now has to see patients on the sly here in his home.”

Hannah nodded but did not tell Ethel she had lost her job, the thought too raw for her to mouth the words. She’d let her family down. Since Papa’s patients were Jews, they could not pay for his services. They needed her money to help them survive.

“And Mama?”

“Upstairs talking with Jacob. The young man has distressed her, but I don’t know why.”

Although the kitchen was warm, Hannah was cold, and she left her sweater on. “I’ll drink the coffee later. I’ll see if I can give Papa some help with his last patients.”

“Mrs. Goetz may lose her baby. She’s with the doctor.”

Hannah questioned why with her eyes.

“Not enough nourishment. They are struggling to exist. So unjust. The Nazis forced them to close their business. I’m preparing extra soup for her to take with her, but I’m afraid she’ll give it to her two children at home.” Ethel sighed and stirred the soup faster.

Her father greeted her as she entered the room he had converted for his patients with Mrs. Goetz at his side. “My dear, you’re home safe.” He patted her cheek. “You know Mrs. Goetz.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Not too well. The doctor says I must rest and eat.” She gave him a weak smile. “Much easier said than done.”

“Mrs. Oster has soup for you and you must promise to eat some. Come into the kitchen.” Hannah took her by the arm. “You should have a bite before you leave.”

After Mrs. Goetz ate a small bowl of soup, Ethel sent her on her way with enough for the family for supper. Hannah returned to her father’s examination room where he checked the last patient, a beautiful brown-eyed girl accompanied by her mother. She had a bad cold and wheezed.

“Keep her in bed, make a tent over her, and use hot water to create steam. There is little I can do for a cold. I can’t even provide you with cough medicine.” Dr. Dresser sucked in his breath and blew it out, his frustration apparent to Hannah.

“As soon as Daniel finds work, we’ll pay you,” Mrs. Helmenstine said.

“Don’t worry about it. With conditions for us as they are, we can only survive by helping one another. Take care of little Sadie.” Dr. Dresser took the child’s hand. “You stay in bed and follow your mother’s orders. Do take care on your way home.”

When they left, Hannah cleaned the room, wiped down the metal with hot water, and folded the sheet covering the exam table. She avoided looking at her father who shuffled papers and filed reports, his face grim. Life was unjust.

“You must have bad news to tell me,” he said, without looking at her.

“I’ve lost my job at the hospital because I’m a Jew. I won’t be able to contribute to our living. Oh, Papa, I’m terrified for us. What will we do?”

“I could lie and tell you everything will work out in the end. We only need keep our faith, but under the Nazis I have no hope. I’m at a loss as how to fight the menace facing us. Fortunately, I have some savings that will help.” Her father gave her a hug, but without assurances things would improve. “The hospital has lost an excellent nurse.”

“You, Mother, and Jacob could leave Germany, go to a country where you’d be safe.” Hannah did not include herself. Whether she saw Penn or not, she could never leave him. Her love for him was too deep not to know what happened to him, even if she only saw him from a distance.

“My patients need me. I’m one of the few doctors left who will care for them. It’s out of the question.” He busied himself with making notes on patient charts.

“May we sit for a minute? I have something to tell you.” Hannah guided him in the direction of his chair behind his desk and sat opposite him.

Unease registered in his eyes. “No more bad news, I hope. You weren’t mistreated. I could not bear that for I’m helpless to do anything.”

“No. As I walked home, I witnessed Storm Troopers dragging a young woman down the street. German citizens followed taunting her, calling her a Jew lover, a traitor to the new order. The SS hit her legs with batons, kicked her feet to make her stumble. I could do nothing to help her.” Hannah choked on the sob in her throat. “I left, afraid I might be noticed as a Jew. I was a coward. The young woman did nothing but love a Jew.”

“My dear daughter, there is nothing you could have done. You were right in leaving. You might have been hurt or arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Himmler tells us the camps are models of descent treatment to the prisoners. I have heard otherwise. We must keep a low profile to survive.” He stood, came around his desk, and put his hand on Hannah’s shoulder.

“Don’t consider yourself a coward.”

“I have more to tell you.” Hannah covered her father’s hand with her hand. She strained to say the next words. Agreeing to no longer see Penn broke her heart, left her empty, and without hope. “I won’t see Penn any longer.” The words stumbled out of her. “I love him, but I agree with you.”

“I’m sorry for you, but it’s for the best. His father is a Nazi as Penn may be. We can’t trust them or Penn. Any day, he or someone in his house may denounce us or report me for continuing to practice medicine against the orders of the Nazis.”

Hannah glanced at her father in surprise. “Penn would never report us. He loves me. I love him. Someday we’ll be husband and wife.” Her stomach pained with reality. She and Penn would never marry, and she would lose contact with him.

“You’re a Jew. We’re Jews. We can’t believe in such nonsense. You’ll never marry him. If relations between Jews and Ar

yans were allowed, you still could not marry him.” He paused and returned to his chair. Resting his elbows on the arms of the chair, he continued, “Thank you, my daughter, for considering our safety by staying away from Penn. Now, I have some better news. Jacob has been hired temporarily by a munitions factory to work on a rocket design.”

Hannah opened her mouth in surprise. She said nothing but her thoughts were terrified for Jacob. Would the owners turn him over to the Gestapo when he finished with his work? They could not risk letting him go free. He could provide details to the English.

“Let’s turn off the lights and go to the kitchen for supper.” Dr. Dresser stood, took Hannah by the hand and led her to the kitchen where they found her mother, Jacob, and Ethel engrossed in conversation.

Hannah glanced at her watch. In two hours, she was to meet Penn for the last time to tell him of her decision.

Jacob nodded in her direction. He was a perfect specimen for the Nazis with his muscular build, his height, his blue eyes, light hair, handsome face with straight nose, and fine mouth, nothing to mark him as a Jew.

Hannah forced a smile. “Papa tells me you’re going to work on a design for a munitions plant. I hope you aren’t taking a risk.”

“I may be, but I’m essential to their undertaking. I’ll need to watch my back.”

“They could force you to do the work without pay.” Dread overwhelmed her. She wanted to beg Jacob to stay away from the project.

“If they did, they could never be certain I wouldn’t sabotage their project. For once, I have the upper hand. They must trust me.”

“I hope you’re not making a mistake,” Hannah said.

Before joining them at the table, Ethel served each of them a bowl of vegetable soup, sweet smelling bread, and butter she had purchased from a farmer. Any barriers between them had disappeared when the Aryan servants left them. She remained without pay and the words, “You’re my only family, all I have. I’ve seen to Jacob and Hannah since they were born.”

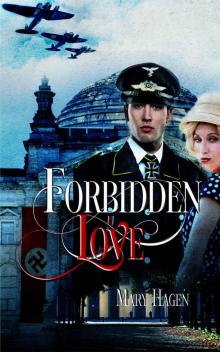

Forbidden Love

Forbidden Love